Miami’s Latino“Entrepreneur Boom” Isn’t a Success Story. It’s a Warning.

Bakery owner Jorge Sactic at his business outside Washington, D.C. Photograph by Beatrice M. Spadacini.

Walk down Calle Ocho or through Hialeah any weekday morning and you will see the same scene on repeat: food trucks opening their windows, abuelas counting change at corner bakeries, contractors loading pickup trucks with tools. For many politicians, this is proof that the system works; that if Latino immigrants just “hustle” hard enough, Miami will reward them with the American Dream. But when analyzed a little closer, one discovers a different scene: entrepreneurs locked into tiny, undercapitalized businesses not because the U.S. legal and financial systems empower them, but because those systems leave them with few other options. In Miami, U.S. immigration law and federally regulated bank‑lending practices do not empower Latino immigrants to “make it” through entrepreneurship. They constrain them both socially and economically. By simultaneously restricting their access to stable wage work and affordable credit, these systems channel them into undercapitalized small businesses that reproduce racial inequality even as their labor and firms prop up the local economy.

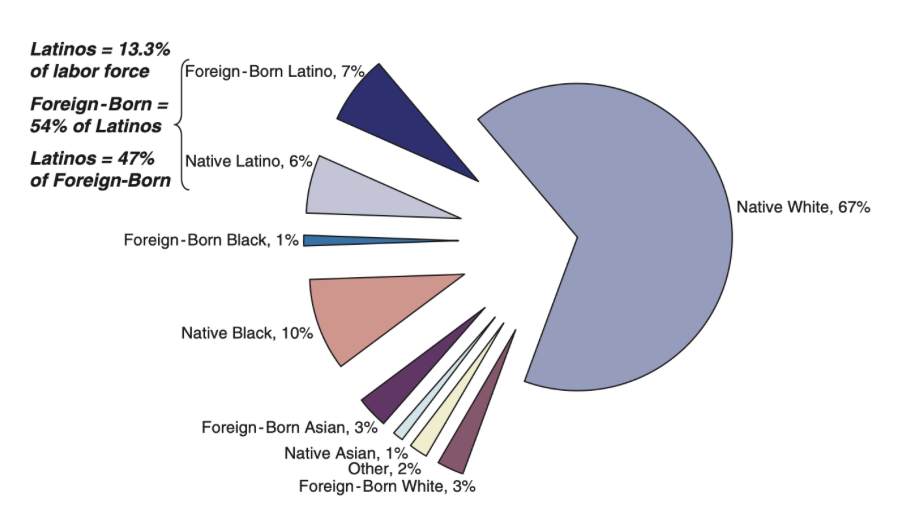

The myth goes like this: Latino immigrants open businesses because they’re “natural entrepreneurs.” However, evidence shows a less romanticized narrative. Labor‑market researchers Lisa Catanzarite and Lindsey Trimble find that Latinos are heavily concentrated in low‑wage, unstable jobs and face higher unemployment and work instability than white workers with similar education. They claim Latinos make up 13.3 percent of the workforce, shown in Figure 1, but almost half of all foreign‑born workers and more than half of those Latino workers are immigrants. Within that percentage, the 1986 Immigration Reform Act made the undocumented workers especially vulnerable, mandating employers to conduct legal status checks. As such, enforcement policies grew to transform an action as easy as getting hired under a payroll into a legal risk. The “choice” to become self‑employed is often a choice between unstable entrepreneurship and no work at all.

Figure 1. Labor force by race/ethnicity and nativity, 2005. Reproduced from Catanzarite and Trimble (2008), using data from the U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics.

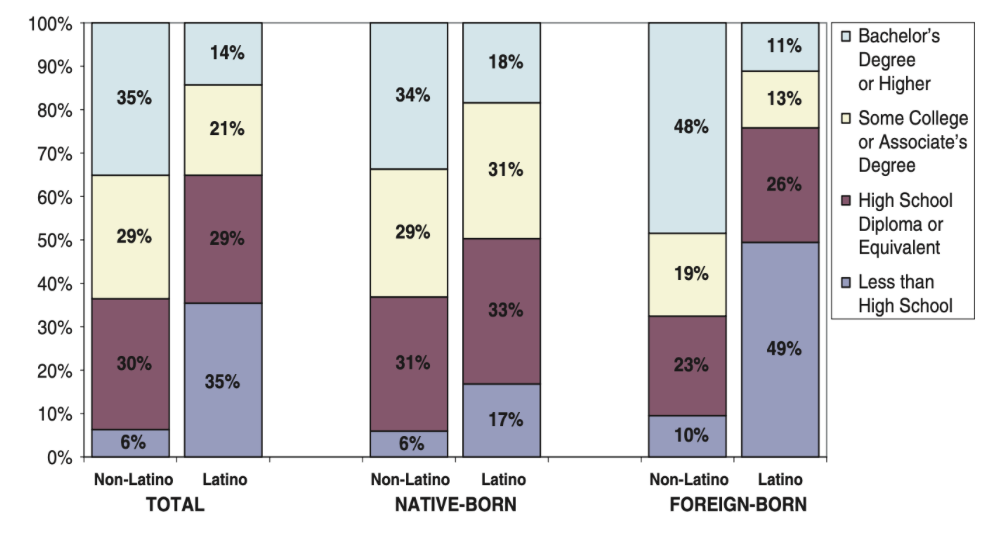

Educational barriers continue to shape unequal labor market outcomes. Catanzarite and Trimble further discuss educational attainment in relation to labor. Figure 2 shows that nearly half of immigrant Latino workers in 2005 had less than a high‑school education. In contrast, non-Latino immigrants made up less than 10 percent. Low formal schooling, combined with limited English for many recent arrivals, narrows access to the professional and union jobs that build wealth over time. Some Cuban and South American migrants arrive with higher education, capital, and business networks. But large numbers of Central Americans, Mexicans, and Caribbean migrants land in a labor market that expects them to clean hotel rooms, pour concrete, or cook in the back of a restaurant for low wage payroll jobs. When those jobs vanish in a downturn, starting a food stand or cleaning business can feel less like the fulfillment of an entrepreneurial dream and more like the last available survival strategy.

Figure 2.Educational attainment of the labor force (ages 25+), non-Latino and Latino by nativity, 2005. Reproduced from Catanzarite and Trimble (2008), based on author calculations using U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

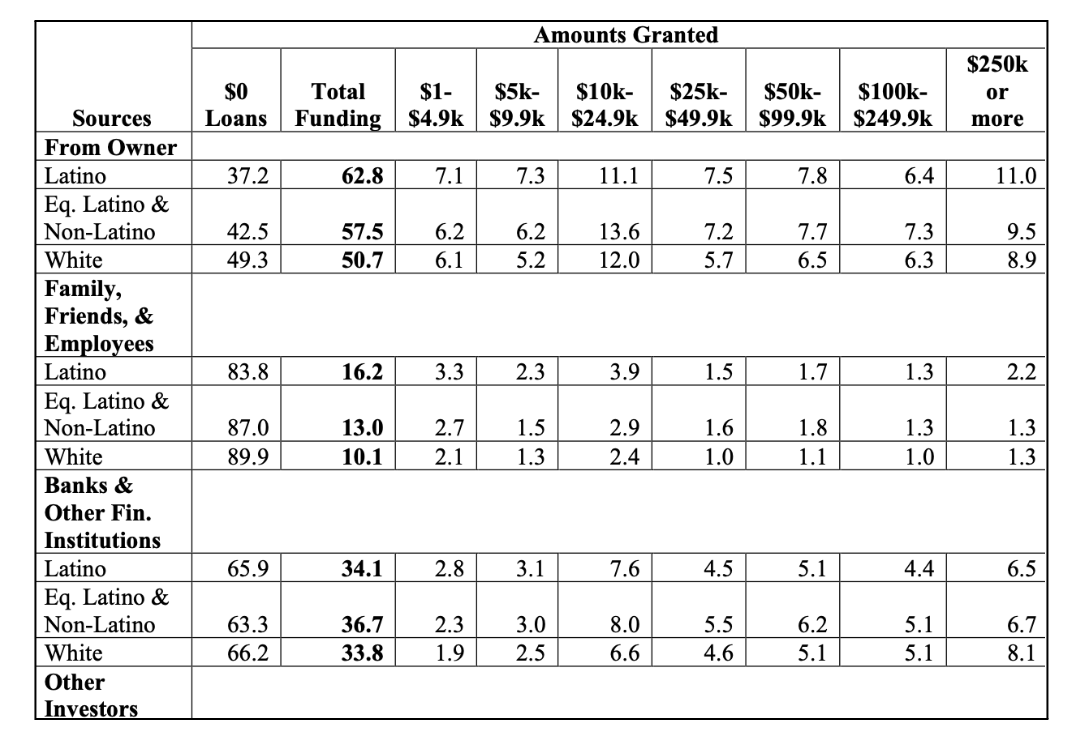

Similarly, researchers Marcelo Siles and Rubén Martinez find that when Latino firms – like privately owned, often owner-operated small businesses – do get credit from banks, it is often in smaller brackets. Table 1 shows that white-owned firms more frequently secure larger loans – including amounts above $250,000; the kind of capital that might let a restaurant build a second location or a small construction company become a regional employer.

Table 1. Funding sources among racial/ethnic business owners by amounts—3-year average (percentages; 2014–2016). Reproduced from Siles and Martinez (2021), using data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of Entrepreneurs.

Clearly, the data shows a trend: there is a disproportionate labor market system. But why do these gaps persist? There are both internal and external factors. On the business side, many Latino entrepreneurs start with low personal wealth, limited prior business experience, and thin credit histories. On the banking side, lenders impose stricter standards, charge higher interest rates, keep branches out of Latino neighborhoods, and fail to hire bilingual, culturally competent staff. The result is a kind of financial redlining for entrepreneurship: Latino‑owned firms are structurally steered toward high‑cost credit cards, family loans, and “buy‑now, pay‑later” arrangements with suppliers – instruments that keep the lights on but rarely fund scalable expansion.

In Miami, that financial redlining looks like the taquería that survives for a decade but never builds a second dining room, the landscaping company that can’t afford a new truck even as demand explodes, the home‑based bakery that can’t move into a commercial kitchen because the bank won’t count cash‑based income as reliable. The city gets the tax revenue and cheap services, while the families who run these businesses get exhaustion and fragile margins. In a city like Miami, where glossy conferences now celebrate “the next Latin tech hub,” that disparity matters. When Venture Capitals (VC) firms scan for “scalable” opportunities, they overwhelmingly back English‑speaking founders with elite degrees and existing wealth – often Latinos in the narrowest sense, or not Latino at all. Meanwhile, Latino immigrant entrepreneurs building steady, unglamorous businesses in food, childcare, transportation, and home repair are branded “lifestyle” or “micro” and are passed over. This two‑tiered system ensures that the upside of Miami’s “Latino boom” flows to a small, already advantaged slice of the population, while the risks of debt, burnout, and legal vulnerability are concentrated among immigrants whose status is most precarious.

If we took Miami’s Latino entrepreneurs seriously as proactive citizens and not just as economic inputs, our policy agenda would look very different. On the legal side, immigration reform would provide work authorization and a clear path to permanent status for the undocumented workers who already clean hotels, cook in restaurants, and run informal businesses across the city. That alone would expand their access to formal employment and reduce the “push” into risky self‑employment documented in the labor‑market research. States and cities could also decouple small‑business licensing and inspections from immigration enforcement, so opening a food truck doesn’t feel like handing your address to ICE. On the financial side, regulators and local governments could treat equal access to credit as a civil‑rights issue, not a niche development problem. That shift means strengthening community‑reinvestment requirements, supporting community development financial institutions (CDFIs) that actually underwrite loans based on cash‑flow rather than perfect credit scores, and conditioning public subsidies for banks and VC funds on transparent reporting of who gets funded – by race, ethnicity, neighborhood, and immigration status. CDFIs often underwrite loans based on cash-flow and business stability rather than perfect credit, making it possible for a food truck or cleaning business with steady income to access affordable capital. Treating credit access as a civil-rights issue would also require banks and venture funds to publicly report who receives funding and on what terms. Additionally, practical reforms that Siles and Martinez discuss, like hiring bilingual staff, opening branches in Latino neighborhoods, and designing flexible products for unbanked and underbanked customers, should be a regulatory floor, not a marketing choice.

Walk down Calle Ocho or through Hialeah any weekday morning, and you will still see ingenuity, discipline, and cultural wealth on full display. What you will not see is a system designed to meet that labor with dignity, stability, or real opportunity. Despite some Latino entrepreneurs thriving, the small percentage of cases should be read as evidence to how unequal starting points, plus biased laws and lending practices, produce a segmented “Latino economy.” Where a few scale up, many are stuck at the edge of survival. The next time we hear politicians crow about Miami as a “Latino entrepreneurship miracle,” we should ask a harder question: miracle for whom? Until immigration law stops criminalizing Latino workers and the financial system stops starving their businesses of affordable capital, entrepreneurship here will remain less a ladder out of inequality than a treadmill that keeps it running.

Alessandra Shires, BC’29, is an Economics major from Miami, Florida. She is passionate about learning the intersection of business and law, with a particular focus on how legal and financial systems shape economic opportunity for entrepreneurs.