The U.S. Patent Pro Bono Program and the Limits of Inclusive Innovation

Intellectual Property Rights & Global Innovation

Patents are a form of intellectual property that serve as a key impetus for research and development within societies. A patent is granted by the government to individuals, giving patent holders the legal right to exclude others from “making, using, offering for sale, or selling” an invention. Economists widely agree that patent rights are crucial for stimulating the economy, as it incentivizes innovation and investment, generating trillions to the U.S. economy each year. Yet access to patent rights is unequal. In 2023, the Patent Public Advisory Committee under the U.S. Patent Trademark Office (USPTO) found a gap in the distribution of patent holderships. They report that a trend within patent holderships is the disproportionate representation of “women, minorities, and low-income [innovators]” compared to the high rates from high-income white men. They assert that engaging these groups in the invention and patent licensing process would quadruple the rate of innovation and add trillions to the U.S. economy.

Intellectual property rights are embedded in the U.S. Constitution to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries” (Article I, Section 8, Clause 8). Questions then emerge: who are the “Authors and Inventors” who get to enjoy this right? And to what extent do income, race, and gender shape innovation in the U.S.? Women, minority groups, and low-income individuals across the U.S. have the potential to generate an addition of at least 12.5% of the current economic activity produced by patent holders, yet they have been historically excluded from the patent system. The U.S. patent system is indeed dominated by only a few groups of people across the country. Socioeconomic gaps in the patent system hinder innovation and economic growth, and reveal the interlocking impact of wealth, gender, and race within the system of innovation in the U.S. Fortunately, viable solutions exist to narrow these gaps and broaden access to innovation.

Gaps in the U.S. Patent System

An overwhelming majority of U.S. patent holders are in the top income percentiles of the country, and predominantly white males. This reality highlights a disadvantage many low-income individuals and people of color face when attempting to license their creations. From 1970 to 2006, Black inventors in the U.S. were granted 6 patents per million people, compared to an overall national rate of 235 patents per million. Similarly, studies from the Congressional Research Service on “Equity and Innovation” as of 2022 show that around 2018, White Americans were about three times more likely to become inventors than African Americans (the latter conclusions do not stem from recent developments). The patent gap extends even further into income inequality, with recent studies indicating that individuals from high income families are around nine times more likely to file a patent than individuals from low income families, and four times as likely to file a patent than middle-income families. This data suggests a potential correlation between low-income households and patent holdership. When controlled for demographics such as low-income households composed of African Americans, Latinos, and other marginalized groups, this association seems to yield stronger disparities.

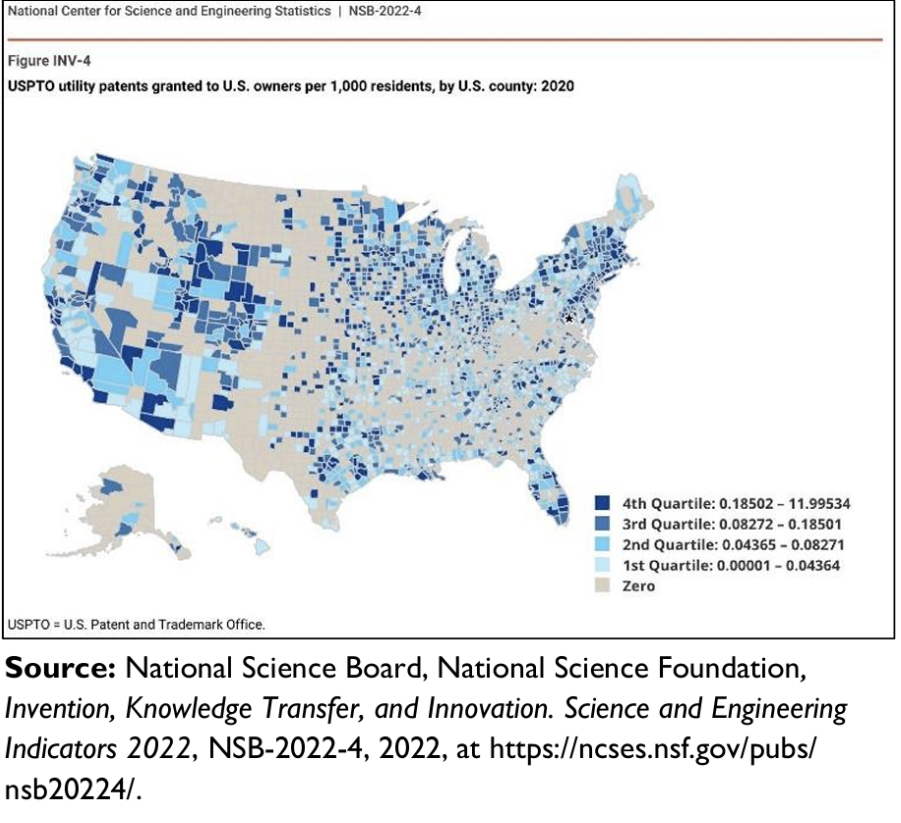

Figure 1. USPTO Utility Patents Granted to U.S. Owners Per 1,000 Residents, by U.S. County. Data from 2020.

Figure 1 depicts the uneven distribution of “utility” patents – the most common form of patents known as “patents for innovation.” This figure shows a key trend: areas of high patenting intensity in the U.S. are primarily concentrated along the coasts, in parts of the Rocky Mountains and Great Lakes as well as Texas. The report also found that an overwhelming 41.6% of U.S. counties had zero patents granted to residents in that county. The top three counties for patenting intensity were Westchester and Schenectady in New York and Santa Clara in California. Population differences aside, this figure supports the earlier association between patent distribution and income, as the data suggest that patent ownership intensity favors wealthier parts of the U.S. This trend is concerning and represents a reality in which innovation and economic growth in the U.S. remains limited.

Innovation has a Price Tag

To no surprise, patent application and prosecution fees alone can cost an individual hundreds, as it requires extensive knowledge of legal documentation which would be very difficult for an average person to understand without a patent advisor or attorney to guide them through the process. The USPTO acknowledges that “preparing a patent application and engaging in the USPTO proceedings to obtain the patent requires knowledge of patent law and USPTO procedures.” While many individuals in the top quintile would easily hire professionals to streamline the process, those who cannot afford the additional costs of an attorney throw out their ideas and creations. As a result, those who cannot file for a patent face the unfortunate reality that jeopardizes their intellectual property, either leaving individuals susceptible to exploitation and theft, or abandoning any notion to introduce their own inventions to the public and claim ownership over their own inventions.

Current Efforts to Narrow the Patent Gap

In 2011 under the America Invents Act, the USPTO established the U.S. Patent Pro Bono Program, meant to address the issues of low income accessibility to patent inventions across the country. The program works in different regions across the U.S. as a network of independently operated programs matching volunteer patent attorneys and agents with financially under-resourced inventors, and small businesses to provide free legal assistance to secure patent protection. Although each regional program under Patent Pro Bono may have different guidelines for admissions, the USPTO has provided a general list of common requirements, including criteria in income, knowledge, and invention. Applicants must have their gross household income be less than three times the federal poverty level, a demonstrated understanding of the patent system either by obtaining a certificate training course or having a provisional application on file, and have the ability to describe their invention and how it works. In 2023 alone, the U.S. Patent Pro Bono Program matched more that 4,400 inventors with a patent practitioner, and from 2015 to 2023, legal professionals under the program have filed nearly 2,240 patent applications on behalf of their pro bono clients. These small yet effective efforts prove that with more outreach and volunteer involvement, the Patent Pro Bono Program has the potential to grow far beyond its current scope.

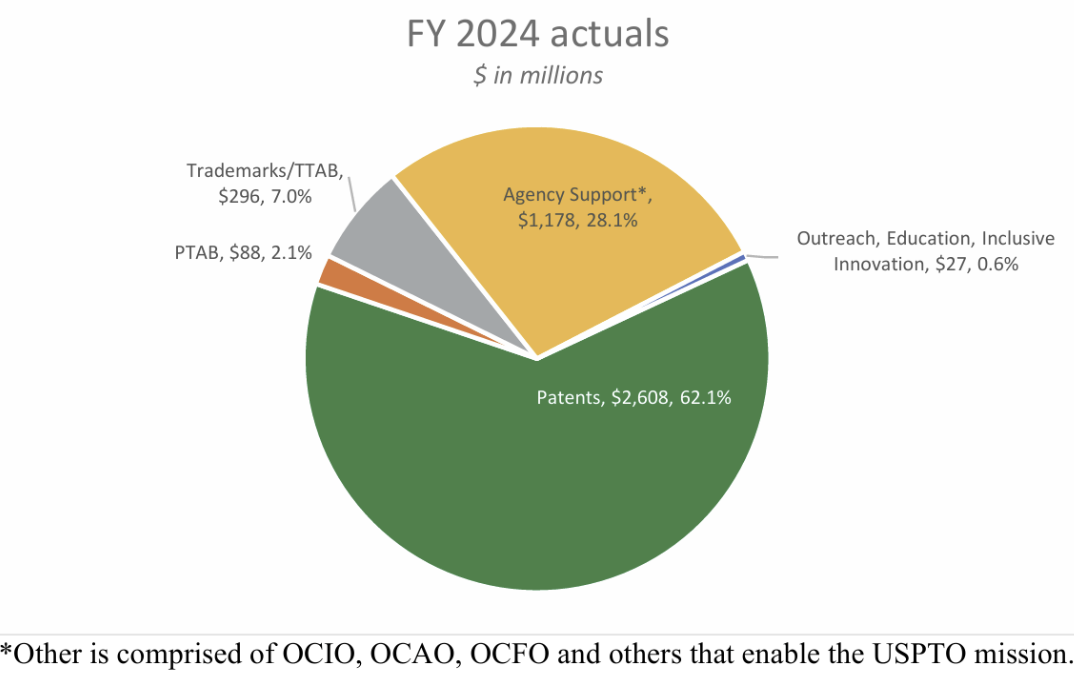

Figure 2. 2024 PPAC Annual Report on USPTO Fiscal Year Spending. Data from 2024.

Although the Patent Pro Bono Program has had some success over the years, it faces many challenges in certain regions, due to the fractional nature of the patent pro bono system. Figure 2 illustrates these limitations using data from the USPTO’s budget allocation for the 2024 fiscal year. The chart shows how outreach initiatives, education, and inclusive innovation are concerningly small, highlighting a need for the USPTO to increase its initiatives for a more successful and inclusive program. Because the pro bono program is operated by region rather than centralized and standardized initiatives, many regions may run the pro bono program less efficiently than others. Regions that may be limited in attorney engagement, inadequate outreach, and logistical barriers that hinder its effectiveness might not be applying methods that are more successful in other regions, leading to many underprivileged communities missing out on the opportunity to utilize their local patent pro bono program. Nevertheless, the program opens new avenues for thinking about how increased engagement has and can be better achieved.

New York City as a Case Study

New York City has proven to be a highly successful program, incentivizing attorney participation with a state bar requirement of at least 50 hours of pro bono service per year for each attorney, as recommended under the American Bar Association. The New York City Bar’s Patent Committee also holds various events throughout the year, including pro bono workshops, sessions with judicial clerks, and continuing legal education courses to keep the community updated on revisions to patent law. As of July 2025, former NYC mayor Eric Adams established the Mayor’s Office to Facilitate Pro Bono Legal Assistance, a “city supported initiative that partners with agencies, law firms, law schools, and community organizations to make legal services accessible to low-income New Yorkers.” Outreach initiatives and volunteer incentives have proven to be significant ways to promote patent pro bono participation in New York City.

New Approaches to Implement

A limitation of the program has been the extent of its outreach efforts. Recently, outreach initiatives have proven to be effective in garnering increased participation rates, as the USPTO reports that even a 6% jump in strengthened awareness and promotion of the patent pro bono program leads to increased participation from historically underrepresented and underserved communities. Studies demonstrated that 43% of patent pro bono applicants self-identified women, compared to only representing 13% of all patented inventors. 35% percent self-identified as Black, 14% as Hispanic American, 5.7% as Asian American or Native Pacific Islander, and 1.6% as Native Americans. Under Patent Pro Bono, the ratio of minority group participation in patent filing becomes more representative of their national presence.

If the USPTO were to expand on its outreach initiatives beyond their current threshold, participation rates would increase proportionately as well. New efforts should target an increase in public awareness through national campaigning. Partnerships with universities, incubators, community organizations, and media outlets could partner with their regional program to inform potential participants in an effort to expand regional collaboration within the Patent Pro Bono Program, as well as the expansion of volunteer networks by recruiting more patent attorneys through commonly used incentives like New York City’s required pro bono participation and continued legal education credits.

Historically, programs such as SNAP have had highly successful national turnouts because of the outreach campaigns funded by the federal government. The creation of this outreach campaign allowed food banks “ to contract with their state or a state-designated nonprofit organization, such as a food bank association, to conduct outreach and receive reimbursement for some of their administrative expenses for these activities by USDA funds.” In turn, after the national campaign, around 60% of member food banks conducted SNAP outreach and application assistance. In the same way that Patent Pro Bono targets underserved populations, SNAP successfully performed large-scale outreach initiatives that expanded the network of aid and information for lower income communities. SNAP’s national success at disseminating critical information to target communities becomes a blueprint for the USPTO to follow, as their primary objective should be to reach larger audiences and create a greater impact.

Reflecting on Systematic Barriers to Innovation

This research brief suggests that income and patent accessibility are correlated, revealing the racial and socioeconomic disparities that exist. The brief also identifies the U.S. Patent Pro Bono Program as a compelling initiative to narrow the patent gap. The right for someone to have and protect their intellectual property is deeply tied to interlocking systematic factors that preclude some groups from accessing such rights. These insights therefore point us to a different perspective on the issue – isn’t the law supposed to protect us all and grant equal rights? It seems that such rhetoric is much more complicated and nuanced in real life than in pure legal philosophy. When there is a monetary barrier blocking the legal protection of one’s intellectual rights, we must consider the underlying systematic frameworks that have deterred innovation for many. Income inequality, racial inequality, and geographic inequality are deeply rooted issues in the U.S. that reveal themselves in both direct and indirect ways – one being access to intellectual property rights. But before any major strides are taken to narrow this gap, there are ways to engage with Patent Pro Bono, such as volunteering or simply spreading word of your regional program, to create a forward movement with their initiative. As we work to narrow the patent gap in the U.S., we must always consider how seemingly major improvements might only be treating symptoms of a much larger problem.

Sophia Shahinaz Sarkies, CC ’29, is a Staff Writer majoring in Economics and English and Comparative Literature. She is interested in intellectual property rights and equity within contract law and labor and employment law.